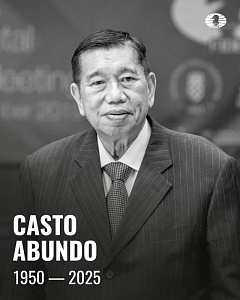

The global chess community recently absorbed the difficult news of the passing of Casto Abundo (1950-2025), former Executive Director of the Asian Chess Federation (ACF). While grandmasters command the spotlight, Abundo belonged to a vital, often-unseen cohort: the technical administrators who build the institutional scaffolding necessary for the sport to thrive. His career was a masterclass in diplomacy, organization, and navigating the chaotic early days of professional chess governance.

The Architect of Asian Stability

Abundo’s impact was most profound in Asia. Serving as Vice-President (2006–2014) and later as Executive Director of the ACF, he was instrumental in transforming the regional chess structure from a disparate collection of national bodies into a cohesive and robust federation. His initiatives laid the groundwork for decades of development, fostering a rare spirit of shared purpose and mutual respect among national federations—a considerable feat in any continental governing body.

His administrative lineage within the sport dates back decades. Achieving the title of International Arbiter in 1978, Abundo quickly moved into high-level organizational roles. His exceptional capacity for logistics was proven repeatedly at some of chess’s most pressure-filled events, including the 1992 Chess Olympiad in Manila, the tumultuous 2000 World Championship cycle, and the 2001 World Cup. These events, massive in scale and fraught with technical and political challenges, operated smoothly largely thanks to individuals like Abundo functioning behind the velvet ropes.

The Era of Analogue Chess Diplomacy

Abundo’s tenure at the top echelons of FIDE management offers a fascinating glimpse into the pre-digital age of global sports governance. He served as FIDE Secretary from 1988 to 1990, working closely alongside the legendary FIDE President Florencio Campomanes. When reflecting on those years, Abundo often noted the stark difference between his operational era and the modern landscape:

“Sometimes it amazes me when I recall how Campo and I managed the chess world without email or mobile phones… We worked 25 hours a day, eight days a week.”

This anecdote is not mere hyperbole; it is a technical testament to the relentless, manual effort required to coordinate international tournaments and policy across dozens of countries using only telegrams, faxes, and landline diplomacy. This intensive, relationship-based style of management defined Abundo`s approach, prioritizing direct human connection over digital efficiency.

A Response to the ‘Prima Donnas’: The Knockout System

While often seen as a bureaucratic stabilizer, Abundo was also an innovator keenly aware of the sport’s commercial and political realities. One of his most enduring contributions stemmed from a controversial problem: the high risk posed by top players threatening to withdraw from Candidates Matches, leaving organizers financially stranded and events decimated.

To combat this—and inject fresh competitive drama—Abundo proposed the now-familiar World Cup knockout system to then-President Kirsan Ilyumzhinov. This format, which pits a massive field of competitors against each other in rapid succession, successfully diluted the singular power held by a handful of star players, ensuring that the show, as they say, must go on. It was a politically savvy and technically brilliant move that secured the viability of major FIDE tournaments.

The Month with Bobby Fischer

Perhaps the most compelling chapter of Abundo’s career was his close, personal involvement with Bobby Fischer during a critical period. In 1976, while Campomanes was attempting to revive the highly anticipated match between Fischer and Karpov, Abundo was given an assignment that went far beyond typical administrative duties: to be Fischer`s constant companion and coordinator in the Philippines for an entire month.

This was administration refined to the level of personal service. Abundo’s month included duties that ranged from the routine to the absurd: playing racquetball with the enigmatic former champion, enduring long, intense discussions on chess theory, swimming far into the open seas, ensuring Fischer was comfortable, and—in perhaps the most unusual administrative task—arranging a date with a Filipina national chess team member the American admired. Abundo even drove Fischer to the yacht of President Marcos, managing the volatile interaction between two powerful, high-stakes personalities.

This unique experience showcases the full spectrum of Abundo’s talent: he was not just an Arbiter of rules, but a highly effective operator capable of managing the greatest, and most difficult, egos the sport had to offer.

Casto Abundo’s passing represents a great loss. His professional legacy—one of stability, growth, and organizational excellence—is deeply embedded in the structures of modern FIDE and the Asian Chess Federation. His work ensured that chess could transition successfully from the analogue Cold War battleground into a professionalized global sport, often doing the necessary, unglamorous work that allowed the masters to compete.